LIL’WAT

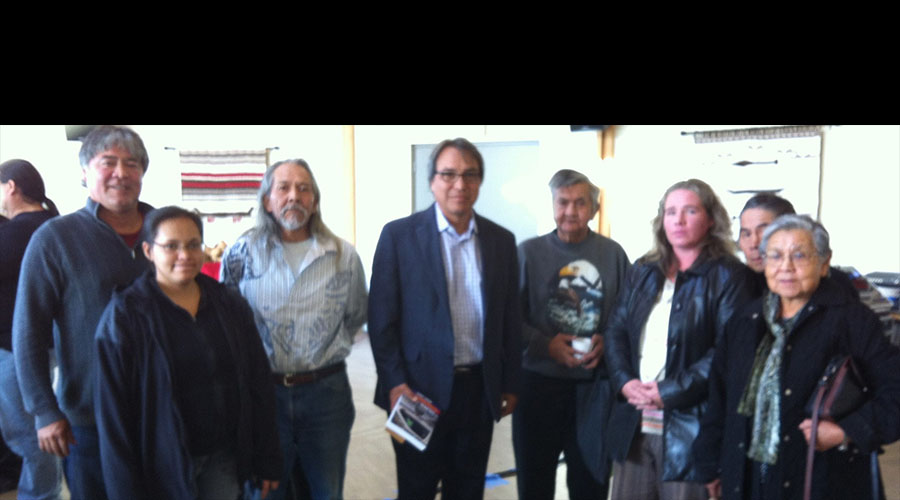

Tracey Robinson, IACHR Commissioner on the Rights of Women (back) meets with IHRAAM-IACHR petition instigator, James Louie (far eft), Loni Edmonds, left) and Kerry Coast (right)at the Renaissance Inn, Vancouver on August 9th, 2013 concerning Edmonds v. Canada case at the International Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)

May 24, 2022. Lil’wat elder James Louie, primary instigator of IHRAAM Petition to the IACHR, Edmonds vs. Canada, Case 12.929, personally hands documents re case to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as Trudeau visits site of an unmarked burial ground at the former Kamloops, B.C. residential school. A video of the event can be viewed here:

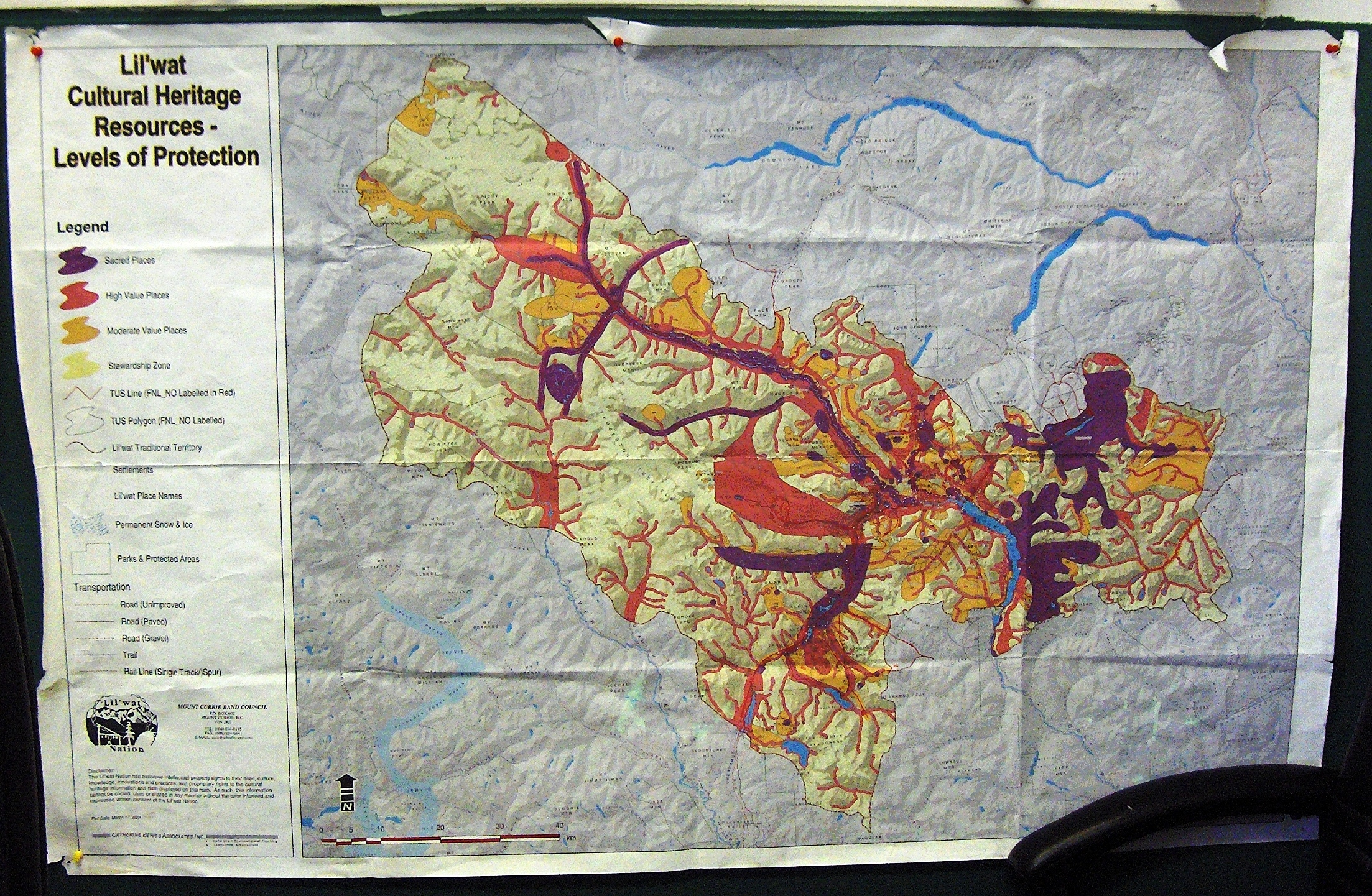

Like most indigenous nations in BC, the Lil’wat do not have a treaty with Canada. They have consistently asserted their right to self-determination as a free and independent nation. Canada unilaterally imposed its jurisdiction upon the Lil’wat through Canadian legislation (The Indian Act) as well as a system of band councils which it recognized as indigenous governing authorities instead of the traditional leadership.

Via this instrumentation, Canada has exercised de facto jurisdiction over indigenous children and families, leading to its intensive and intrusive scrutinization of indigenous parents, to disproportionate child seizure and to largely unscrutinized foster care placement — to strikingly deleterious effect.

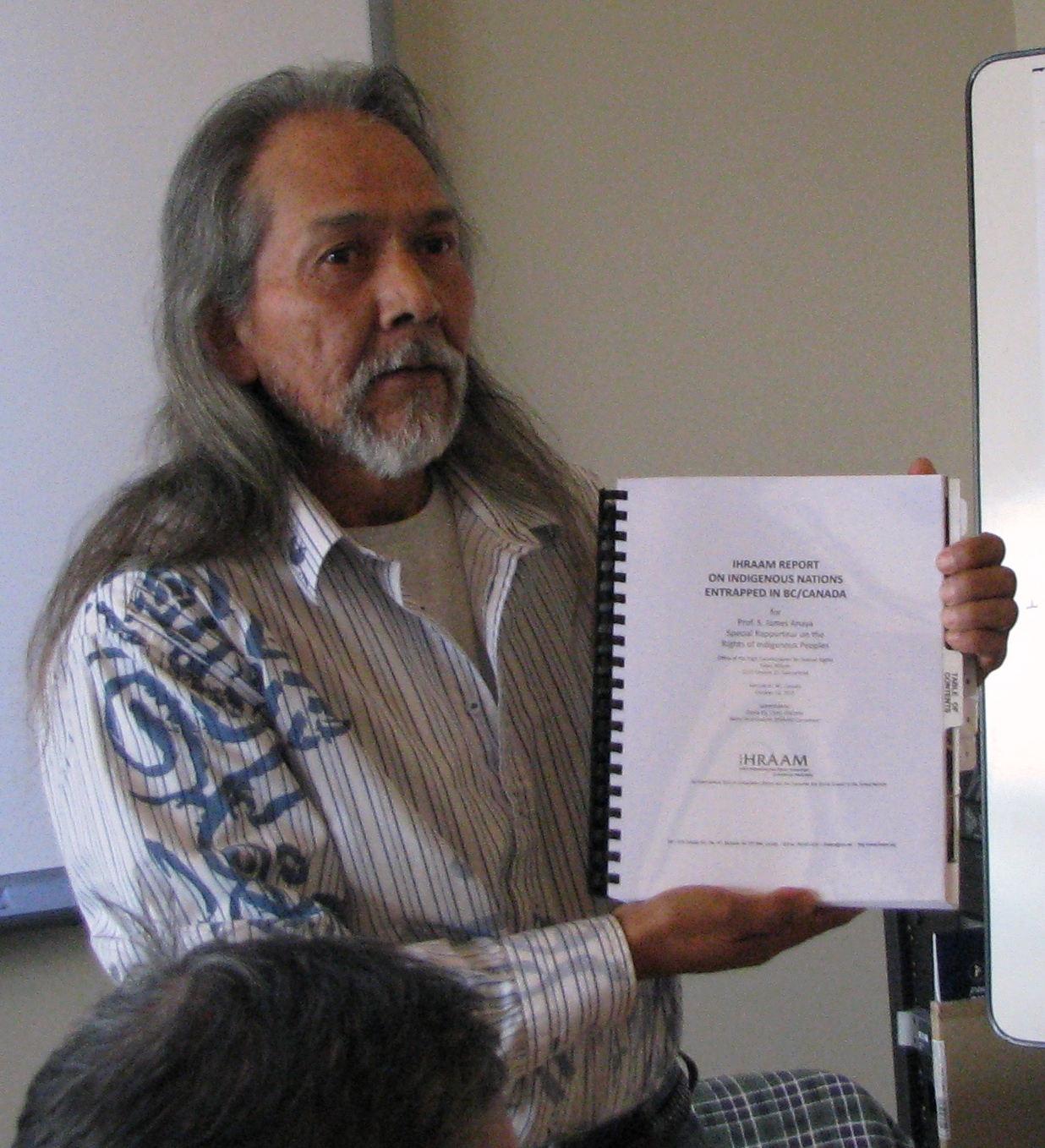

In this context, in 2007, the IHRAAM International Legal Clinic submitted a Petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) on behalf of Lil’wat mother, Loni Edmonds, in relation to the seizure of her children by the BC Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) and their placement in foster care.

The IACHR is a principal and autonomous organ of the Organization of American States (“OAS”) whose mission is to promote and protect human rights in the American hemisphere. It is composed of seven independent members who serve in a personal capacity. Created by the OAS in 1959, the Commission has its headquarters in Washington, D.C. Together with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (“the Court” or “the I/A Court H.R.), installed in 1979, the Commission is one of the institutions within the inter-American system for the protection of human rights (“IAHRS”).

In its Petition to the IACHR, IHRAAM argued that because it was impossible to raise in Canadian courts the jurisdictional issue of whether Canada had lawful jurisdiction over Lil’wat families and children, and the right to make the policy, laws and enforcement resulting therefrom, Ms. Edmonds could not get a fair trial in Canadian courts. Not only could the jurisdiction issue not be raised due to the legal principle of Nemo Potest Esse Simul Actor et Judex, but also the inability to do so had been empirically proved over a history of actual attempts to raise it.

In 2011 the IACHR advised that it had submitted the Edmonds Petition (Loni Edmonds 879-07) to Canada for its response. When Canada responded several months later, the IACHR requested, received and submitted IHRAAM’s Observations on the Canada Response back to Canada; Canada then again responded (twice), and on June 21, 2012, IHRAAM again submitted its Observations 2 to Canada’s second response. On July 30, 2012, Canada responded again, and, as requested by the IACHR, IHRAAM submitted further Observations on the fourth Canada response. On September 20th, 2012, the IACHR informed IHRAAM that these Observations had again been passed on to Canada for its response and that Canada had been given one month to respond. IHRAAM awaited further word of Canada’s fifth response.

By communication dated January 23, 2014, the IACHR advised IHRAAM that it has admitted the case, forwarding to IHRAAM its Report on Admissibility No. 89/13. and opening the case Edmonds v. Canada.

As a result of continuing MCFD actions, Loni Edmonds has not only lost her six children, but also her place of residence, as she was viewed as no longer entitled to the degree of housing support that she had enjoyed when living with her children. She has been effectively homeless since 2007 and living on a monthly stipend of $235. There is a waiting list of over 200 persons for single person residence on her Reserve. As she has no home, her homelessness remains a barrier in her long struggle to regain custody of her children.

This case is extremely significant not just in relation to the well being of indigenous children in Canada, who continue to be placed in Foster Care at nearly three times the numbers of Residential School placements at their peak. It is germane to the issue of investment and development in BC, insofar as corporations must decide whether they will respect indigenous nations’ sovereignty, or continue to follow the practice of Canada in signing resource-related agreements outside of legitimate treaty settlements. While BC and Canada have set in motion a number of processes and mechanisms to try to resolve what is recognized as the “uncertainty” surrounding Canada/BC’s legal title to land, resources and jurisdiction in British Columbia, their success has been minimal. Even the Indian Act-empowered indigenous governments have been reluctant to accede to the terms offered, which in the guise of “treaties” appear to require extinguishment of indigenous sovereign rights and title.